Growing Up With Sacred Forests

Sacred Grove is a term I grew up with, hearing it in the local Kannada language as Devara Kaadu (God’s Forest) and Naaga Bana (Snakes’ Forest). We were told never to trespass, and we obeyed without questions, curiosity, or even a second thought. Looking back, that unquestioning obedience feels almost miraculous in today’s world, where even “No Entry” signs seem to invite negotiation.

When Fear Became Conservation

These sacred forests make far more sense now, especially as we continue to dismantle our environment in the name of development. After visiting the Mawphlang Sacred Forest in Meghalaya, my respect for our forefathers deepened considerably. They must have foreseen what lay ahead and responded with remarkable foresight, declaring certain forests sacred and strictly forbidding any alteration. To ensure compliance, they wrapped conservation in stories of curses, blessings, and ominous consequences. Fear, it turns out, was an early and highly effective environmental policy.

The Meaning Behind Mawphlang

Among the Khasi people, these sacred groves are known as Lawkyntang. Our guide explained that Maw means stone and Phlang means grass. An apt name, as the rocks here are blanketed in soft green moss. The forest spans 192 acres and lies about 25 km southwest of Shillong. “If you walk straight through,” the guide said casually, “you can reach Cherrapunji on the other side.” I discreetly consulted Google Maps to verify this ambitious claim.

A Forest on a Historic Path

Interestingly, one of Meghalaya’s historic horse tracks laid by British administrator David Scott to connect Assam to Sylhet (now in Bangladesh) runs through Mawphlang. Today, hikers can trek 16 km of this once-100 km route, from Mawphlang to Lad Mawphlang.

Asking Permission to Enter

The forest is divided into three sections. Only local Khasis are allowed into the first two (Laittyrkhang and Law Nongkynrih). The third section, Phiephandi, is open to tourists, but only if accompanied by a guide. Before entering, like all locals, we stop at monoliths near the entrance to pay our obeisance – a formal request for permission to enter the forest. This Sacred Grove of the Hima Mawphlang kingdom is governed by a council of twelve elders, each representing a clan, led by a member of the Lyngdoh clan.

Labasa, The Spirit Who Watches

Once inside, we are instructed to stay on the stone path built specifically for visitors. The reason becomes clear almost immediately. Apart from the risk of getting lost, the forest is dotted with sacred monoliths, and accidentally disrespecting one is the last thing any visitor wants to do. Central to the belief system here is the powerful spirit deity Labasa, who is said to bless or punish depending on one’s actions. Nothing, absolutely nothing, is allowed to be taken out of the forest. Not a leaf, not a twig, not even a pebble. Disobedience invites consequences that Labasa administers personally. There is no idol or image of this deity, only belief. When I mentioned we were Mangaloreans now living in Bangalore, our guide smiled and gently referenced the movie Kantara. I understood exactly what he meant, no further explanation required.

Eight Centuries of Biodiversity

The forest is astonishingly rich in biodiversity. It is home to over 400 species of plants and trees, including 40 varieties of orchids. We saw ancient Rudraksha trees, oak, rhododendron, yew, silver palm, pine, chestnut, and more. No surprise, given that the forest has stood for over eight centuries. Even fallen trees are left undisturbed, as per tribal law. The fauna includes birds, monkeys, civets, snakes, deer, and leopards. Spotting a leopard, especially after a ritual, is considered a good omen; encountering a snake, not so much.

Rituals of the Past

Rituals (from coronations to sacrifices) were once held regularly in the forest. Elders carried all required paraphernalia in one go because leaving midway was not an option; unlike today, where forgotten items can be summoned with a tap on a phone’s screen. Stone tables – flat stone slabs resting on short vertical stones served as the final checkpoint to review supplies before entering the most sacred area.

As part of the ritual, a bull would be sacrificed to appease Labasa. The bull had to meet strict criteria – young, healthy, free of deformities, brown in colour and raised in one of the tribal villages. The bull was tied to a huge Chinese Bayberry tree with a large canopy near the sacrificial altar (photography prohibited). The Lyngdoh king was required to kill it with a single swing of his sword. Women were not allowed in the forest or to witness the ritual. The bull’s heart and blood were offered at the altar, while the rest of the meat was cooked in plain water (no salt, no spices, no embellishments) and shared among those present. Leftovers were not permitted to leave the forest.

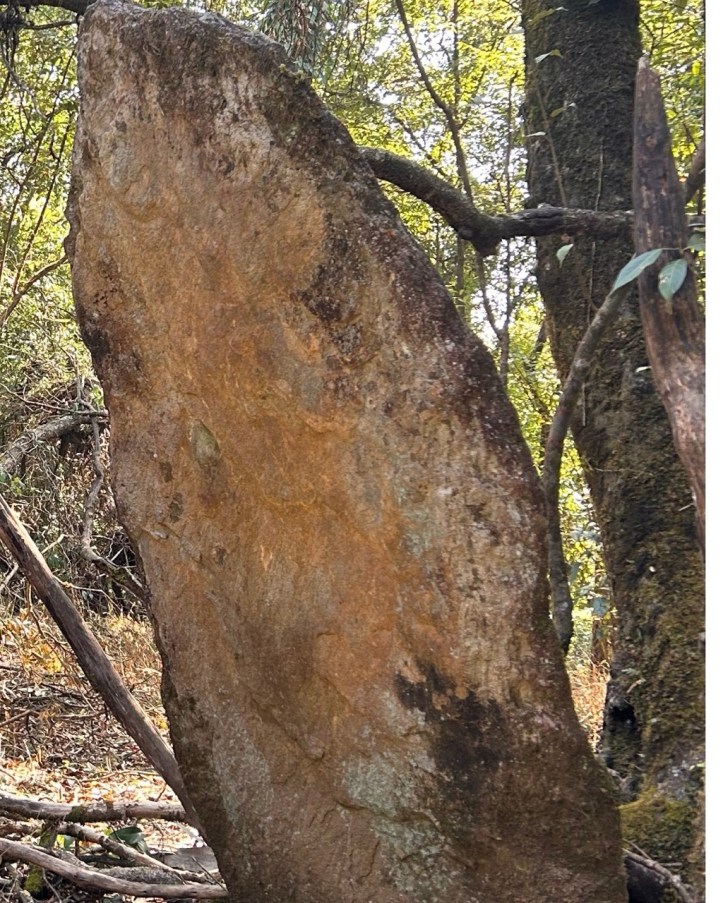

The Sacrificial Altar and the Menhir

Animal sacrifice is understandably a sensitive subject, with strong opinions on both sides. In Mawphlang, the last bull sacrifice took place in 1959. Since then, a rooster is sacrificed on a hill closer to the village, outside the forest. The Chinese Bayberry tree has since fallen and, in keeping with tribal law, remains exactly where it fell. The sacrificial altar stands beside it, marked by a tall menhir that continues to stand as a silent witness for posterity. If you look beyond the walking path, you can spot smaller monoliths camouflaged by moss and dense foliage.

Where the Forest Stops

Sacrifice aside, sacred groves like Mawphlang are the reason certain tree species have survived and entire ecosystems continue to thrive. Our guide mentioned that the forest does not expand beyond an invisible boundary, beyond which open grasslands begin. When we visited, the grassland glowed a rich golden hue; during the monsoon, it turns a vivid green.

Lessons From a Sacred Grove

I learned more from this single visit than I currently know about the Devara Kaadu and Naaga Banas of my own hometown. Mawphlang is not just a forest; it is a living lesson in conservation, belief, and restraint. I commend Meghalaya and the Khasi people for opening this sacred space to the world, allowing us to learn that sometimes, the best way to protect nature is not by controlling it, but by revering it and occasionally, by being just a little afraid of divine consequences.

Note: Dedicating this post to a dear friend who shared the Naaga Bana pic, a few months before he passed.